At the Annapolis boat show, I had a conversation with friends who are planning a full refit, but are not intending to pull the chainplates. I said something about new rigging not meaning a thing if it is attached to chainplates that are going to give way and pointed out that crevice corrosion is going to happen exactly where you cannot see it, as the plate passes through the deck. They argued that the metal they could see looked great and that checking the chainplates would require dismantling some of the interior wood and joinery, which would, obviously, be a colossal and potentially costly piece of work.

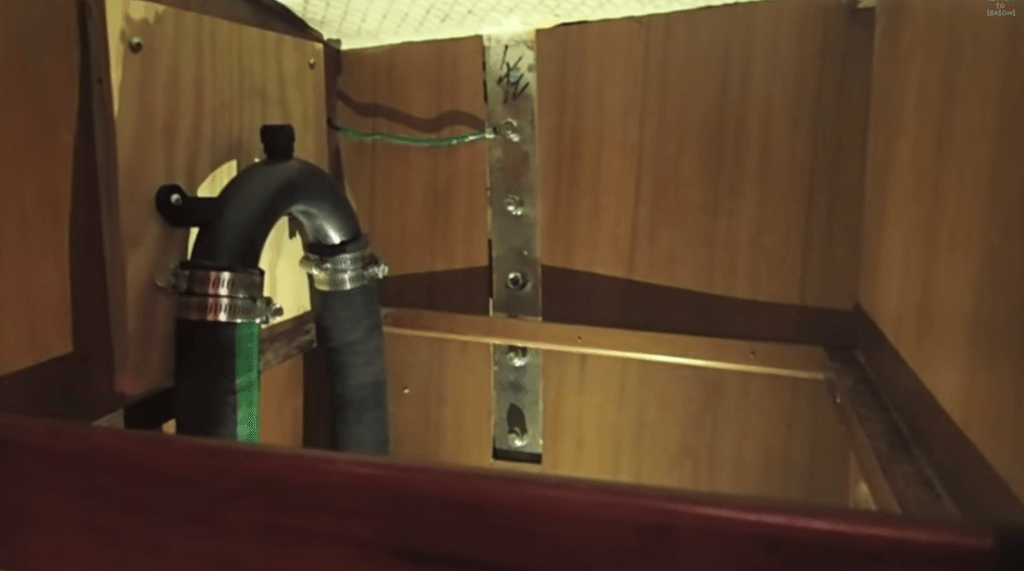

Fortunately for us, this was about as much of the cabinetry that we had to remove in order to get at the chainplates.

I try to avoid telling people what they should be doing with their boats, partly because I know I am no expert and partly because I cannot stand when people do that to us. The conversation about the chainplates proved to be one of those instances that really tested my ability to keep my opinions out of other people’s boats. But I did – for better or for worse – and now I am cathartically sharing some of my thoughts on the subject.

Over the years, I received a number of reader messages related to chainplates (reader messages on much of anything are rare, but chainplates are a leading subject for them). In most of the emails, folks inquire about how we removed our plates or how we installed the external chainplates. But a few of the writers shared harrowing tales of narrowly averting a disaster caused by chainplate or knee failure.

One guy, Gary, told me about being under sail in 20 knots and seeing the backstay abruptly shift four inches. He managed to get in without losing his rig. Gary had recently replaced all the other chainplates, but the backstay plate. I never found out exactly what happened, but I would bet the chainplates and bolts were in good shape, but had shifted in the rotten wood of the knee. On Bear, we only discovered that our aft knee was waterlogged when we were installing the external chainplate for the backstay. I have imagined what would have happened had we not gone through the hassle of replacing the chainplates; we could have been a lot worse off than Gary.

The knee of the backstay chainplate with rust around each one of the bolts. This was the knee that ended up being waterlogged and needed to be grinded out.

Another correspondent, John, related how, after debating whether it was worth the effort, he had finally decided to remove the chainplates while re-rigging the boat. The first plate that he tried to pull out cracked in half before he could remove it from the boat. Incredibly, all the other chainplates appeared fine, but he ended up replacing them all nonetheless. John’s experience also struck a chord. When I put a ratchet on the nut of the first chainplate I removed on Bear, I sheared the bolt off the knee. All the rest of our couple dozen bolts seemed fine, but that one experience convinced us that we needed to move to external chainplates.

Replacing the chainplates with external chainplates was the most difficult and stressful job that we have done on our Tayana 37 so far, and hopefully it stays that way. I also recognize that removing chainplates can be even more difficult on other boats, especially those with glassed-in chainplates that require some grinding just to get them out. But checking the knees and chainplates – and I would really argue replacing the latter regardless, because it is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to see corrosion in some cases – is an essential part of any refit.

This was the worst-looking chainplate we pulled from Bear. After polishing it up, though, I could not see any corrosion on it. We obviously replaced them all anyway.

Stainless steel corrodes when wet and starved of oxygen. That means that stainless steel chainplates are most vulnerable to corrosion right where they go through the deck, in the exact spot where you cannot visibly inspect the plate. Thus, the only way to ensure that chainplates are in good condition is to pull them. And once the chainplates are out, inspecting the knees makes a lot of sense as well.

If you are lucky, your knees are just fiberglass or a solid piece of wood with a backing plate. But on the Tayana 37 and quite a few other boats, the knees are wood embedded in fiberglass. These require drilling some inspection holes to ensure there is no moisture in the knee. In our experience, drilling between the two upper bolts and at the bottom of the knee revealed the waterlogged wood, whereas the holes we drilled on the sides of the bolts turned up dry.

I guess this post is something of a public service announcement. I think I wrote it hoping to alleviate some of the ambivalence I felt about my encounter at the boat show. On one hand, I have some guilt about not more adamantly urging my friends to replace their chainplates. But, on the other, I certainly do not want to be the guy who holds forth as an expert, telling other people what they need to do to their boat. Regardless, I think inspecting and replacing chainplates is necessary.

Thank you for your posts.

What are your thoughts on the wooden mast? Please email me if you can take some time to talk….